With no less than 65 tractor brands each sporting a large number of models on offer to Australian landholders, how does a person judge machine against another? Farm machinery guru Dr. Graeme Quick is on the case.

When it comes to tractor selection criteria, cost isn’t necessarily the first or best one to prioritise. Even if you were to buy the lowest-cost model in the size you’re after, how much will this machine cost in the long-haul?

These are important questions: after all, apart from the land itself, machinery is the most expensive capital component of the professional farmer’s business.

On issues such as seed or fertiliser, mistakes can be buried in one season, whereas machinery purchase decisions have an impact for many years after. Purchase price is just the beginning.

Objective Assesment Criteria

Let’s put one matter to rest from the outset: there are no tractors or combine harvesters made in Australia. Not a single one, so home-brand loyalty doesn’t enter the equation.

To me the most interesting machines are combine harvesters. When people quiz me about which is the best harvester to buy, the immediate response is: “Who is your dealer and where is he?”

If the response is satisfactory on that important account then consider other factors like size and power matched to the operation etc. The assessment can be summarised as the six Ps: Price; Power; Parts; Performance; Persistence; Prestige — and Parsimony.

The literal order among these priorities depends to some extent on who is buying. Is the purchaser a broadacre landholder, a contractor, a rental agency, or a ‘backyard baron’.

Consider the small acreage landholders and backyard barons first. There are two very different classes of machines offered, based on two categories of users: the hobby farmer running say 200 hours a year and the professional farmer who runs up say 500 hours or more a year.

For the first clientele, the landholder running a machine for say 200 hours a year or less, manufacturers make machines that are lighter, less rugged and cheaper. These are ‘consumer’ products.

Many are sold by outlets which may not have any back-up services. Such stores cannot provide repair and maintenance (R&M) services.

The second category of products is ‘commercial’ machines, designed to last longer and built for tougher conditions. These are usually sold by dealers with back-up services. These represent good value for the small-area user, but they do come at a cost.

The retail price of tractors ranges widely, from some $400 to over $1,200 per horsepower ($530 to $1,610 per kW). That’s not much of a guide.

As an example, the 2013 New Holland tractor series is pretty much on line at $758 per horsepower. What really counts is value for money, and getting value for money requires a buyer to be well informed before taking the plunge.

Factors to consider

There are many kinds of price deals offered at tractor dealerships, like package pricing, model-release timing, options, and of course trade-in considerations.

How much power you need is governed by the equipment hitched on to the tractor. There are definite advantages to buying a bit more power than anticipated.

The higher-powered machine for a given acreage may cost more but it should last longer and will provide greater satisfaction. Frustrations arise when a lower-powered tractor proves too slow for the task or some tasks turn out to need more ‘oomph’. That’s especially the situation when you get your first front-end loader.

Ready availability of parts and service is especially critical for professional users. Machine downtime affects seasonal operational timeliness. Having a trustworthy dealer close by is important.

Performance involves such things as field capacity (see below), engine torque rise and lugging ability, gear range, implement linkages, hydraulics output, and power take-off (PTO).

Tractor reliability affects downtime, which is directly related to seasonal performance. A professional, commercial-wheeled ag tractor should be capable of around 10,000 to 12,000 hours.

Prestige is a bit hard to quantify. Certainly some machines look better or simply are superior to others in the same category. Bragging rights are not to be overlooked.

Lamborghini anyone? (That company got its start in tractors — but today Lambos are not necessarily made in Italy or by the up-market car company.)

In relation to parsimony, professional farmers always need to rein in costs. Fuel often looms large in the accounting.

Tractor owners can keep operating costs down by effective field work organisation. This means ballasting to manage wheel slip; suitable gear selection; appropriate implement matching; systematic machinery maintenance, and so on.

Owning and Operating Costs

The two principle cost streams are first, ownership costs, and second, operating or ‘variable’ costs.

Also known as ‘fixed’ or overhead costs, ownership costs accrue essentially whether the machine is working or not. Fixed costs include depreciation (the difference between purchase price and salvage or trade-in value), interest, taxes, insurance and shedding costs. Don’t just look at depreciation as a drop in value only, but consider accounting for the cost of replacing the machine later.

The costs of a (new) replacement machine increase 2 or 3 per cent a year whereas by contrast the old machine is depreciating at 15 per cent or more each year.

It’s important to charge yourself an ‘interest on investment’ cost; after all, you could take the dough invested in the machine and instead bet on a nag in the Melbourne Cup. That interest charge is appropriately also called an ‘opportunity cost’.

Taxes, insurance and storage or shedding costs typically amount to around 2 per cent of purchase price.

The second cost stream, operating or ‘variable’ costs include R&M, fuel and lubricant, and labour. These variable costs are in direct proportion to hours of use. R&M costs depend on location, operator habits and whether the tractor is kept under roof.

R&M costs escalate with accumulated hours on the meter. In the absence of precise data tractor fuel costs for diesel engines can be roughly estimated from this formula: Litres per hour = 0.16 x Max PTO. Lubricants add up to around 15 per cent of fuel costs.

Total costs are accordingly the sum of the fixed and the variable costs.

Effect of hours of use on cost

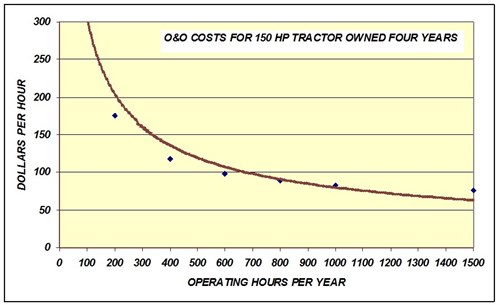

To illustrate, compare the two categories of users — a hobby farmer running say 200 hours a year and the professional farmer who runs up to say 600 hours a year.

If each of those users purchased a 55hp (40.5kW) tractor that tractor, when used for 200 hours a year and kept for five years, would cost $74.60 per hour.

While for the full-time farmer or a contractor using the same machine for 600 hours a year, the cost would be $42.40 per hour.

Can you afford that tractor?

It boils down to this: how much do you need to spend to get your tractor or machinery work done or get your crop into the ground and harvested in optimal time?

A profitable farmer will manage the operation to complete the cropping cycle yet keep his machinery costs down. The real costs of ownership can be staggering.

There can be better ways to put capital to work, especially when some of that machinery is under-utilised. A tractor that runs up 400 hours in a working year is barely reaching 20 per cent utilisation.

No profitable factory could stay in business with equipment only worked for 20 per cent of the time — idle for 80 per cent of the time.

Ownership ties up valuable capital that might be better or more profitably applied to land, debt reduction, or some other form of diversification. Options to ownership include leasing, equipment hire, rental, sharing, machinery rings – or using a contractor. Those options can also mean access to the very latest technology.

If you’re in business — can you really afford to own that tractor?

|

Dr Graeme Quick is an international expert in farm machinery. Over the past 40 years he has held senior positions at Iowa State University, CSIRO and NSW Department of Agriculture. He’s also a best-selling author. Nowadays he holds various engineering consultanices and, with his wife, lives on acreage in Peachester in south-east Queensland where they grow cabinet timbers and fruit trees. He can be contacted at g.quick@bigpond.com. |

This article was initilaly published in NewFarmMachinery magazine issue 5, December 2013. For the latest farm machinery news, reviews and informational features, subscribe to NewFarmMachinery magazine.